Neonatal Resuscitation: What does it mean?

Neonatal resuscitation is vital for a baby’s survival immediately after birth, helping to stimulate breathing and provide the necessary support.

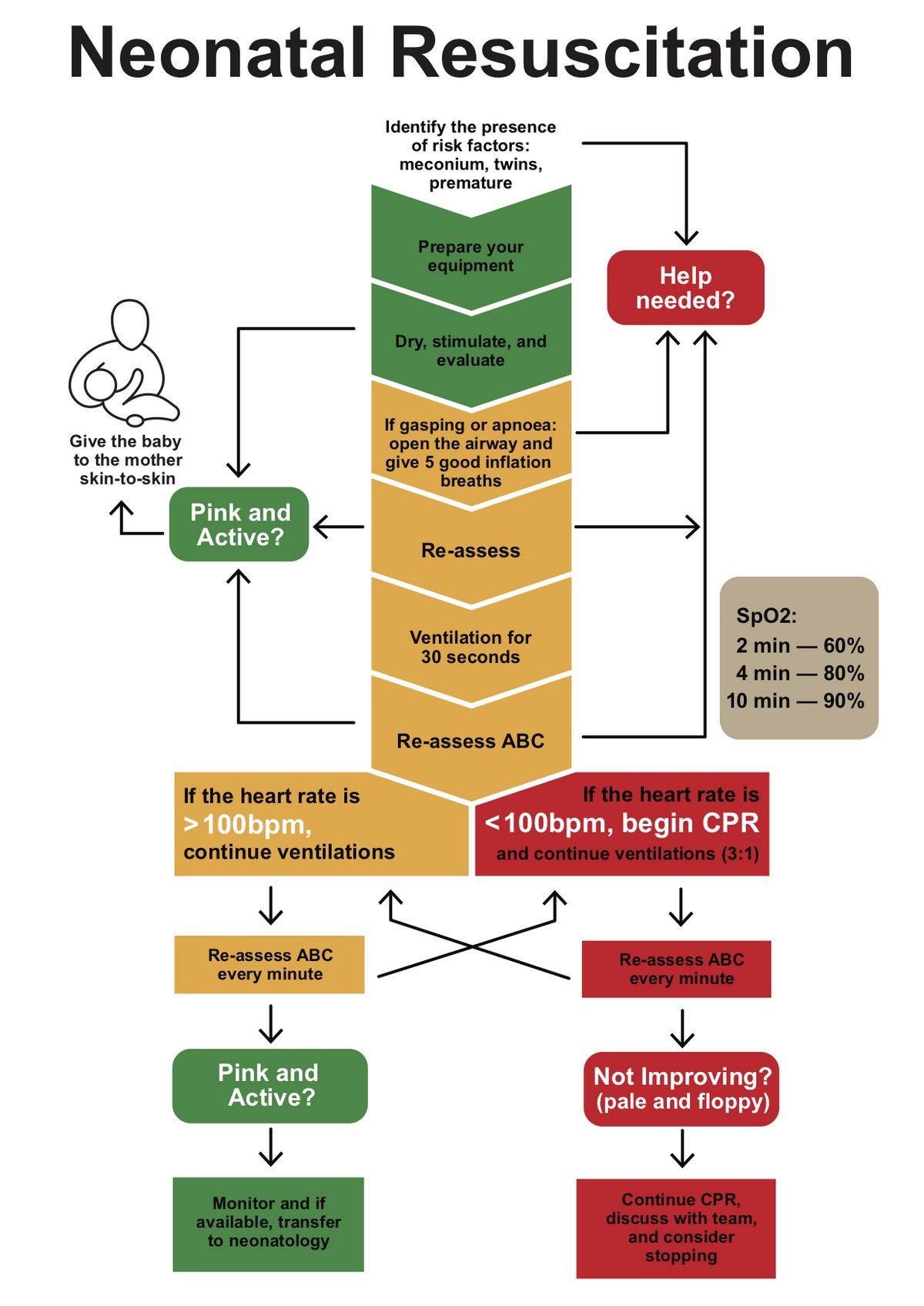

While some newborns only require basic measures like warmth, clearing the airway, and gentle stimulation, others may need more advanced techniques such as CPR with assisted ventilation and chest compressions.

In the United States, about 10% of newborns need some form of assistance during the transition from fetus to newborn.

Why is neonatal resuscitation important?

In cases of oxygen deprivation or extreme prematurity, neonatal resuscitation becomes necessary for the baby’s survival. Acting rapidly and effectively within seconds after birth is crucial under these circumstances.

The objectives of neonatal resuscitation are:

- Providing oxygen

- Stimulating respiration

- Promoting cardiac function and adequate blood flow

- Maintaining core temperature

- Ensuring proper blood glucose levels

Various physiological changes occur before, during, and immediately after birth, enabling a baby to breathe and sustain life outside the uterus. Prematurity or illness may delay or disrupt these changes, necessitating the need for neonatal resuscitation.

Two significant systemic changes during the transition from fetus to newborn are:

Respiratory adaptation

Prior to birth, fetal lungs are nonfunctional, and gas exchange occurs in the placenta. As the fetus changes position and undergoes contractions during labor, some of the fluid in the lungs is expelled. Hormonal secretions during birth aid in stopping fluid secretion, promoting its reabsorption and drainage.

A substance called surfactant, which is produced in the lungs, reduces surface tension in the alveoli (air sacs). This prevents their collapse when the fluid is expelled, enabling the baby to take their first breath. Mechanoreceptors and chemoreceptors stimulate the respiratory center in the brain, leading to continued respiration.

Cardiovascular adaptation

Immediately after birth, the fetus transitions from a right-to-left blood circulation to a left-to-right circulation when the baby breathes for the first time. In fetal circulation, there are three shunts that facilitate blood flow: the foramen ovale, the ductus arteriosus, and the ductus venosus. These shunts close shortly after birth.

Oxygen-rich blood from the placenta flows through the umbilical vein to the fetus. While some blood perfuses the liver, most of it bypasses the liver, enters the inferior vena cava through the ductus venosus, and reaches the right upper chamber of the heart. From there, the blood flows into the left atrium, left ventricle, aorta, and the rest of the body, bypassing the still-constricted pulmonary vessels.

When the newborn takes their first breath, pulmonary vessels dilate due to the increased oxygenation, enhancing blood flow between the heart and the lungs. This, in turn, leads to closure of the shunts and establishes left-to-right circulation.

When should neonatal resuscitation begin?

Immediate assessment of the newborn’s condition after birth is crucial in determining the need for neonatal resuscitation. If the following characteristics are present, routine postnatal care suffices:

- The baby has completed full-term gestation.

- The amniotic fluid is clear, with no signs of infection or meconium (baby’s first stool).

- The baby starts crying and breathing.

- The baby has good muscle tone.

If any of these criteria are not met, doctors initiate neonatal resuscitation immediately.

What are the steps involved in neonatal resuscitation?

The following steps are taken sequentially, as necessary, during neonatal resuscitation:

- Initial stabilization, which includes:

- Providing warmth

- Clearing the airway with suction

- Drying the baby

- Gently stimulating the baby to breathe

- Additional interventions may include:

- Epinephrine to increase heart rate and blood pressure

- Saline solution to increase blood volume

What neonatal resuscitation techniques are controversial?

The Neonatal Resuscitation Program (NRP), developed collaboratively by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American Heart Association (AHA), has established standardized procedures for neonatal resuscitation.

However, ongoing evaluation of these standards has led to ongoing controversies, including:

- Room air versus 100% oxygen: While some studies suggest that resuscitation with room air is as effective as using 100% oxygen, the use of either one lacks sufficient supporting data. Additionally, high concentrations of oxygen can cause tissue injury due to oxygen-free radicals.

- Artificial surfactant administration: Surfactant deficiency contributes to respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), particularly in extremely premature infants. There is a debate regarding the timing and preventive use of surfactant administration, which may be expensive for infants who do not require it. Current recommendations suggest administering surfactant within the first few minutes of life for infants born before 28 weeks of gestation or showing signs of RDS.

- Intubation and suctioning for meconium aspiration: The NRP previously recommended routine suctioning of all non-vigorous infants born in meconium-stained amniotic fluid as soon as the head is delivered. However, current guidelines advise suctioning only if there is visible thick meconium in the nose and mouth.

- Hypothermia: Some studies propose that slightly cooling the heads of asphyxiated infants could reduce brain injury. However, this contradicts the need to prevent hypothermia for effective neonatal resuscitation and requires further investigation.

- Withholding and discontinuing resuscitation: Advances in technology have improved the survival rate of extremely premature infants. Decisions regarding withholding or discontinuing resuscitation are difficult, involving considerations of viability and ethics, and are made in consultation with parents.

When should neonatal resuscitation be discontinued?

Based on current guidelines, neonatal resuscitation is typically discontinued if there is no detectable heart rate or respiration after 10 minutes of continuous and appropriate resuscitative efforts. However, in certain cases, resuscitation may be continued for up to 20 minutes, considering factors like the presumed reason for cardiac arrest, gestational age, presence of complications, potential role of therapeutic hypothermia, and parental preferences regarding associated risks of morbidity.

Nonetheless, individualized decision-making is key, and studies indicate that resuscitation efforts should generally be withheld for infants with a gestational age lower than 23 weeks, a birth weight less than 400 grams, or certain congenital anomalies (such as anencephaly, trisomy 13 or 18) associated with almost-certain early death.